About XPC

XPC is, first and foremost, about doing things in a different way than you'd otherwise be able to do them. It is less about enabling things that you couldn't do without XPC.

XPC is all about security and stability of our apps. XPC allows us to relatively easily split our application into multiple processes. It does so by making the communication between processes easy. Additionally, it manages the life cycle of processes so that subprocesses are running when we need to to communicate with them.

We will be using the Foundation framework's API defined in the NSXPCConnection.h header. This API builds on top of the raw XPC API, which in turn lives inside xpc/xpc.h. The XPC API itself is a pure C API, which integrates nicely with libdispatch (aka GCD). We'll use the Foundation classes because they let us access almost all of the full power of XPC — they are very true in nature to how the underlying C API works. And the Foundation API is a lot easier to use than its C counterpart.

Where is XPC Used?

Apple uses XPC extensively for various parts of the operating system — and a lot of the system frameworks use XPC to implement their functionality. A quick run of

% find /System/Library/Frameworks -name \*.xpc

shows 55 XPC services inside Frameworks, ranging from AddressBook to WebKit.

If we do the same search on /Applications, we find apps ranging from the iWork suite to Xcode — and even some third-party apps.

An excellent example of XPC is within Xcode itself: When you're editing Swift code in Xcode, Xcode communicates with SourceKit over XPC. SourceKit is responsible for things such as source code parsing, syntax highlighting, typesetting, and autocomplete. Read more about that on JP Simard's blog.

It's actually also used extensively on iOS — but only by Apple. It's not available to third-party developers, yet.

A Sample App

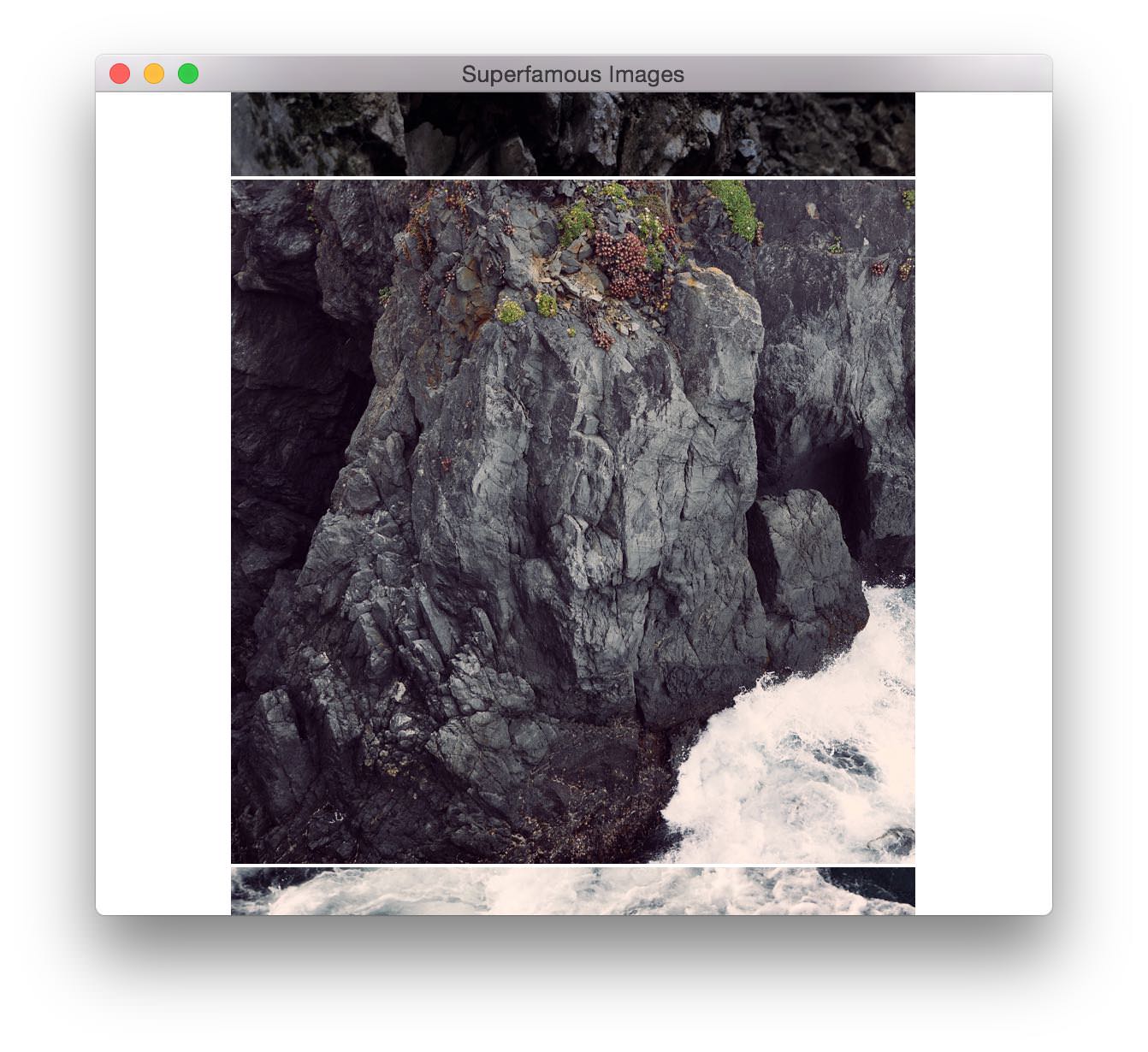

Let us take a look at a trivial sample app: an app that shows multiple images in a table view. These images are downloaded as JPEG data from a web server.

The app will look something like this:

The NSTableViewDataSource will retrieve the images from a class called ImageSet, like this:

func tableView(tableView: NSTableView!, viewForTableColumn tableColumn: NSTableColumn!, row: Int) -> NSView! {

let cellView = tableView.makeViewWithIdentifier("Image", owner: self) as NSTableCellView

var image: NSImage? = nil

if let c = self.imageSet?.images.count {

if row < c {

image = self.imageSet?.images[row]

}

}

cellView.imageView.image = image

return cellView

}

The ImageSet class has a simple

var images: NSImage![]

property, which is filled asynchronously using the ImageLoader class.

Without XPC

Without XPC, we would implement the ImageLoader class to download and decompress an image, like so:

class ImageLoader: NSObject {

let session: NSURLSession

init() {

let config = NSURLSessionConfiguration.defaultSessionConfiguration()

session = NSURLSession(configuration: config)

}

func retrieveImage(atURL url: NSURL, completionHandler: (NSImage?)->Void) {

let task = session.dataTaskWithURL(url) {

maybeData, response, error in

if let data: NSData = maybeData {

dispatch_async(dispatch_get_global_queue(0, 0)) {

let source = CGImageSourceCreateWithData(data, nil).takeRetainedValue()

let cgImage = CGImageSourceCreateImageAtIndex(source, 0, nil).takeRetainedValue()

var size = CGSize(

width: CGFloat(CGImageGetWidth(cgImage)),

height: CGFloat(CGImageGetHeight(cgImage)))

let image = NSImage(CGImage: cgImage, size: size)

completionHandler(image)

}

}

}

task.resume()

}

}

This is pretty straightforward and works well.

Fault Isolation and Split Privileges

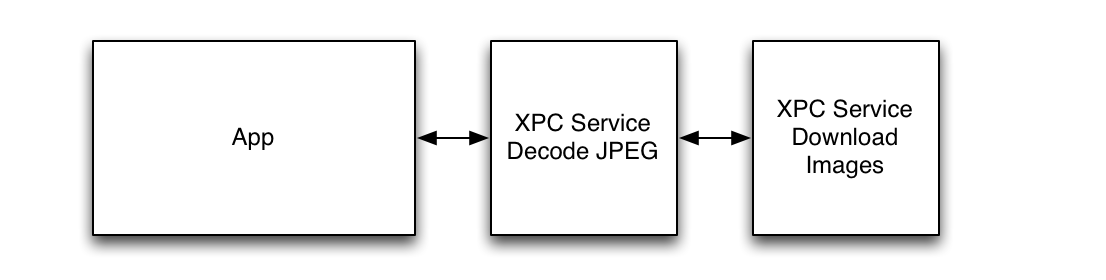

Our app does three distinct things: it downloads data from the internet, it decodes that data as JPEG, and it then displays the data.

If we split the app into three separate processes, we can give each process its own set of privileges; the UI process doesn't need to have access to the network. The service that downloads the images from the network does need network access, but doesn't need access to any files (it will just forward the data, not save it). The second service will decode the JPEG image data to RGB data. This process needs neither network access nor file access.

This way, we have made it dramatically more difficult for someone to find a security exploit in our app. And as a side effect, the app is way more stable; if a bug in the download service causes it to crash, the main app will keep running, and the download service will just get relaunched.

This might look something like this:

We could also have designed it so that the app would talk to both services directly and be responsible for moving the data from one service to the other. The amount of flexibility is great. We'll look into how an app locates services later.

By far, the largest set of security-related bugs is in the parsing of untrusted data, i.e. data that we have received, for example, over the Internet, and do not control. This is true for both handling the actual HTTP protocol and decoding JPEG data. With this design, we have moved parsing of untrusted data into a subprocess, an XPC service.

XPC Services at Our Service

There are two parts to the service: the service itself, and the code that communicates with it. The good news is that both are straightforward and similar to one another.

Xcode has a template to add a new target for a service. A service has a bundle identifier. It is good practice to set it to a subdomain of the app's bundle identifier. In our case, the sample app's bundle identifier is io.objc.Superfamous-Images, and we will set the bundle identifier of the download service to be io.objc.Superfamous-Images.ImageDownloader. The service target will create output in its own bundle, which will get copied into a folder called XPCServices, next to the Resources folder.

When the app sends data to the io.objc.Superfamous-Images.ImageDownloader service, XPC will automatically launch the XPC service.

Communication over XPC is always asynchronous. It is defined by a protocol that both the app and the services use. In our case:

@objc(ImageDownloaderProtocol) protocol ImageDownloaderProtocol {

func downloadImage(atURL: NSURL!, withReply: (NSData?)->Void)

}

Note the withReply: part. This is how the reply will get sent back to the caller asynchronously. Messages that return data need to use methods where the last part is a withReply: that takes a closure.

In our case, we only have one method call in the service, but we could have multiple by defining multiple in the protocol.

The connection from the app to the services is then created through an NSXPCConnection object, like so:

let connection = NSXPCConnection(serviceName: "io.objc.Superfamous-Images.ImageDownloader")

connection.remoteObjectInterface = NSXPCInterface(`protocol`: ImageDownloaderProtocol.self)

connection.resume()

If we store this connection object in self.imageDownloadConnection, we can communicate with the service, like so:

let downloader = self.imageDownloadConnection.remoteObject as ImageDownloaderProtocol

downloader.downloadImageAtURL(url) {

(data) in

println("Got \(data.length) bytes.")

}

We should use an error handler, though. That would look like this:

let downloader = self.imageDownloadConnection.remoteObjectProxyWithErrorHandler {

(error) in NSLog("remote proxy error: %@", error)

} as ImageDownloaderProtocol

downloader.downloadImageAtURL(url) {

(data) in

println("Got \(data.length) bytes.")

}

That's all there is to it on the app's side.

Listening to Service Requests

The service has a listener, NSXPCListener that listens to incoming requests (from the app). This listener will then create a connection on the service side that corresponds to each connection that the app makes to it.

In main.swift, we can put:

class ServiceDelegate : NSObject, NSXPCListenerDelegate {

func listener(listener: NSXPCListener!, shouldAcceptNewConnection newConnection: NSXPCConnection!) -> Bool {

newConnection.exportedInterface = NSXPCInterface(`protocol`: ImageDownloaderProtocol.self)

var exportedObject = ImageDownloader()

newConnection.exportedObject = exportedObject

newConnection.resume()

return true

}

}

// Create the listener and run it by resuming:

let delegate = ServiceDelegate()

let listener = NSXPCListener.serviceListener()

listener.delegate = delegate;

listener.resume()

We create an NSXPCListener at the global scope (this corresponds to the main function in C / Objective-C). We'll pass it a service delegate that can configure incoming connections. We need to set the same protocol on the connection that we use inside the app. Then we set an instance of ImageDownloader, which actually implements that protocol:

class ImageDownloader : NSObject, ImageDownloaderProtocol {

let session: NSURLSession

init() {

let config = NSURLSessionConfiguration.defaultSessionConfiguration()

session = NSURLSession(configuration: config)

}

func downloadImageAtURL(url: NSURL!, withReply: ((NSData!)->Void)!) {

let task = session.dataTaskWithURL(url) {

data, response, error in

if let httpResponse = response as? NSHTTPURLResponse {

switch (data, httpResponse) {

case let (d, r) where (200 <= r.statusCode) && (r.statusCode <= 399):

withReply(d)

default:

withReply(nil)

}

}

}

task.resume()

}

}

One important thing to note is that both NSXPCListener and NSXPCConnection start out being suspended. We need to resume them once they have been configured.

You can find a simple sample project on GitHub.

Listener, Connection, and Exported Object

On the app's side, there's a connection object. Each time we want to send data to the service, we use the remoteObjectProxyWithErrorHandler method, which creates a remote object proxy.

On the service's side, there's another layer. First there's a single listener, which listens for incoming connections from the app. The app can create multiple connections, and for each one, the listener will create a corresponding connection object on its side. The connection has a single exported object, which is what the app will send messages to as the remote object proxy.

When an app creates a connection to an XPC service, XPC manages the lifecycle of that service. The service is launched and shut down transparently by the XPC runtime. And if the service crashes for some reason, it is transparently relaunched, too.

When the app first creates the XPC connection, the XPC service is in fact not launched until the app actually sends the first message to the remote proxy object.

And when there are no outstanding replies, the system may chose to stop the service because of memory pressure or because the XPC service has been idle for a while. The app's connection will stay valid, and when the app uses the connection again, the XPC system will relaunch the XPC service.

If the XPC service crashes, it will also be relaunched transparently. The connection to it will remain valid. But if the XPC service crashes while a message was being sent to it, and before the app received the response, the app needs to resend that message. This is what the error handler in the remoteObjectProxyWithErrorHandler method is for.

This method takes a closure that will be executed if an error occurred. The API guarantees that exactly one of either the error handler or the message reply closure will get executed; if the message reply closure gets executed, the error handler closure will not, and vice-versa. This makes resource cleanup easy.

Sudden Termination

XPC manages the lifecycle of the service by keeping track of requests that are still being processed. The service will not get shut down while a request is running. A request is considered running if its reply has not been sent, yet. For requests that don't have a reply handler, the request is considered running as long as its method body runs.

In some situations, we might want to tell XPC that we have to do more work. To do this, we can use the NSProcessInfo API:

func disableAutomaticTermination(reason: String!)

func enableAutomaticTermination(reason: String!)

This is relevant if we need to perform some asynchronous background operation inside the XPC service as a result of an incoming request. We may also need to adjust our quality of service in that situation.

Interruption and Invalidation

The most common situation is for an app to send messages to its XPC service(s). But XPC allows very flexible setups. As we'll go through further below, connections are bidirectional, and connections can be made to anonymous listeners. Such connections will most likely not be valid if the other end goes away (due to a crash or even a normal process termination). In these situations, the connection becomes invalid.

We can set a connection invalidation handler that will get run when the XPC runtime cannot recreate the connection.

We can also set a connection interruption handler that will get called when the connection is interrupted, even if the connection will remain valid. The two properties on NSXPCConnection are:

var interruptionHandler: (() -> Void)!

var invalidationHandler: (() -> Void)!

Bidirectional Connections

One interesting fact that's often forgotten is that connections are bidirectional.

The app needs to make the initial connection to the service. The service cannot do this (see below on service lookup). But once the connection has been made, both ends can initiate requests.

Just as the the service sets an exportedObject on the connection, the app can do so at its end. This allows for the service to use the remoteObjectProxy on its end to talk to the app's exported object.

The thing to be aware of, though, is that the system managed the lifecycle of the service — it may be terminated when there are no outstanding requests (c.f. Sudden Termination).

Service Lookup

When we connect to an XPC service, the we need to find that other end that we're about to connect to. For an app using a private XPC service, the XPC system looks up the service by its name within the app’s scope. There are other ways to connect over XPC, though. Let us take a look at all the possibilities.

XPC Service

When an app uses

NSXPCConnection(serviceName: "io.objc.myapp.myservice")

XPC will look up the io.objc.myapp.myservice service inside the app's own name space. This service is local to the app — other apps can't connect to this service. The XPC service bundle will either be located inside the app’s bundle or inside the bundle of a framework that the app is using.

Mach Service

Another option is to use:

NSXPCConnection(machServiceName: "io.objc.mymachservice", options: NSXPCConnectionOptions(0))

This will look for the service io.objc.mymachservice in the user's login session. We can install so-called launch agents in either /Library/LaunchAgents or ~/Library/LaunchAgents and these can provide XPC services in much the same way as an app's XPC service. But since these are per-login sessions, multiple apps running in a login session can talk to the same launch agent.

This approach can be very useful, e.g. for a menu in the [status bar] statusbar to talk to a UI app. Both the normal app and the menu extra can talk to a common launch agent and exchange information in that way. Particularly, when more than two processes need to communicate with each other, XPC can be a very elegant solution.

If we were to write a weather app, we could put the fetching and parsing of weather data into an XPC launch agent. We would then be able to create a menu extra, an app, and a Notification Center Widget that all display the weather. And they'd all be able to communicate with the same launch agent over an NSXPCConnection.

In the same way as with an XPC service, the launch agent lifecycle can be entirely managed by XPC: it will be launched on demand and terminated when it is no longer needed and the system is low on memory.

Anonymous Listeners and Endpoints

XPC has the ability to pass so-called listener endpoints over a connection. This is, at first, very confusing, but allows for a great deal of flexibility.

Let's say we have two apps, and we would like them to be able to communicate with each other over XPC. Each app doesn't know what the other app is. But they both know about a (shared) launch agent.

Both apps can connect to the launch agent. App A creates a so-called anonymous listener that it listens on, and sends a so-called endpoint to that anonymous listener over XPC to the launch agent. App B then retrieves that endpoint over XPC from the launch agent. At this point, App B can connect directly to the anonymous listener, i.e. App A.

App A would create the listener with

let listener = NSXPCListener.anonymousListener()

in a similar way to how an XPC service would normally create its listener. It then creates an endpoint from this listener with:

let endpoint = listener.endpoint

This endpoint can then be sent over XPC (it implements NSSecureCoding). Once App B retrieves that endpoint, it can create a connection to the original listener inside App A with:

let connection = NSXPCConnection(listenerEndpoint: endpoint)

Privileged Mach Service

The final option is to use:

NSXPCConnection(machServiceName: "io.objc.mymachservice", options: .Privileged)

This is very similar to launch agents, but will create a connection to a daemon instead. Launch agent processes are per user. They run as the user and inside the user's login session. Daemons are per machine. An XPC daemon will only have one instance running, even when multiple users are logged in.

There are quite a few security considerations about how to run daemon. It's possible for a daemon to run as the root user, which we should probably not do. We most likely want it to run as some unique user. Check the ["Designing Secure Helpers and Daemons"] TN2083 document. For most things, we won’t need root privileges.

File Access

Let's say we want to create a service that downloads a file over HTTP. We need to allow this service to make outgoing network connections in order to connect to the server. What's less obvious, though, is that we can have the service write to a file without the service having any file access.

The way this works, is that we first create the file that we want to download to inside the app. We then create a file handle for that file:

let fileURL = NSURL.fileURLWithPath("/some/path/we/want/to/download/to")

if NSData().writeToURL(fileURL, options:0, error:&error) {

let maybeHandle = NSFileHandle.fileHandleForWritingToURL(url:fileURL, error:&error)

if let handle = maybeHandle {

self.startDownload(fromURL:someURL, toFileHandle: handle) {

self.downloadComplete(url: someURL)

}

}

}

and

func startDownload(fromURL: NSURL, toFileHandle: NSFileHandlehandle, completionHandler: (NSURL)->Void) -> Void

would then send the file handle over the XPC connection by passing it to the remote object proxy.

Similarly, we can open an NSFileHandler for reading in one process and pass it to another process, which can then read from that file without having file access itself.

Moving Data

While XPC is very efficient, it's obviously not free to move messages between processes. When moving large amounts of binary data over XPC, there are some tricks available.

Normal NSData needs to get copied to get sent to the other side. For large binary data, it is more efficient to use so-called memory-mapped data. WWDC 2013 session 702 covers sending of Big Data, beginning with slide 57.

XPC has a fast path which makes sure data is never copied on its way from one process to another. The trick is that dispatch_data_t is toll-free bridged with NSData. If we create a dispatch_data_t instance that's backed by a memory-mapped region, we can send this over XPC more efficiently. This would look something like this:

let size: UInt = 8000

let buffer = mmap(nil, size, PROT_READ | PROT_WRITE, MAP_ANON | MAP_SHARED, -1, 0)

let ddata = dispatch_data_create(buffer, size, DISPATCH_TARGET_QUEUE_DEFAULT, _dispatch_data_destructor_munmap)

let data = ddata as NSData

Debugging

Xcode has your back covered when you need to debug multiple processes communicating with each other over XPC. If you set a breakpoint in an XPC service that's embedded into our application, the debugger will stop there as expected.

Be sure to check out Activity Tracing. Its API is defined in os/activity.h and provides a way to convey across execution context and process boundaries what triggered a certain action to be taken. WWDC 2014 talk 714, “Fix Bugs Faster Using Activity Tracing,” gives a good introduction.

Common Mistakes

A very common mistake is to forget to resume either the connection or the listener. Both are created in a suspended state.

If the connection is invalid, that's most likely due to a configuration error. Check that the bundle identifier matches the service name, and that the service name is correctly specified in the code.

Debugging Daemons

When debugging daemons, things are slightly more complicated, but it still works quite well. Our daemon will get launched by launchd. The trick is twofold: During development, we will change the launchd.plist of our daemon and set the WaitForDebugger key to true. Then in Xcode, we can edit the scheme of the daemon. In the scheme editor under Run, the Info tab allows us to switch Launch from “Automatically” to “Wait for executable to be launched.”

Now when we 'run' the daemon in Xcode, the daemon will not get launched, but the debugger will wait for it to be launched. Once launchd starts the daemon, the debugger will connect, and we're good to go.

Security Attributes of the Connection

Each NSXPCConnection has these properties

var auditSessionIdentifier: au_asid_t { get }

var processIdentifier: pid_t { get }

var effectiveUserIdentifier: uid_t { get }

var effectiveGroupIdentifier: gid_t { get }

that describe the connection. On the listener side, i.e. inside the agent or daemon, we can use these to see who's trying to connect and deny or allow the connection based on that. For XPC Services inside an app bundle, this doesn’t matter all that much, since only the app itself can look up the service.

The xpc_connection_create(3) man page has a section called “Credentials” which talks about some of the caveats of this API. Use it with care.

Quality of Service and Boosts

With OS X 10.10, Apple introduced a concept called Quality of Service (QoS). It is used to help give the UI a higher priority and lower the priority of background activity. QoS is interesting when it comes to XPC services — what kind of work is an XPC service doing?

Since the quality of service propagates across processes, in most cases we won't have to worry about it. When some UI code makes an XPC call, the code inside the service will get a boosted QoS. If background code inside the app makes an XPC call, that background QoS will get propagated across to the service, too. Its execution will be at a lower QoS.

WWDC 2014 talk 716, “Power, Performance and Diagnostics,” has a lot of information about Quality of Service. It mentions how to use DISPATCH_BLOCK_DETACHED to detach the current QoS from code, i.e. how to prevent propagation.

When an XPC service starts unrelated work as a side effect of a request to it, it must make sure to detach from the QoS.

Lower-Level API

All of the NSXPCConnection API is built on top of a C API. This API is documented in the xpc(3) man page and its subpages.

We can create an XPC service for our app and use the C API, as long as we use the C API on both ends.

It is very similar to the Foundation framework API in concept, though one thing that is slightly confusing is that a connection can both be a listener that in turn accepts incoming connections, and a connection to another process.

Event Streams

One feature that, at this point, is only available to the C API, is the launch-on-demand for IOKit events, BSD notifications, or Core Foundation distributed notifications. These are available to launch daemons and agents.

Event streams are outlined in the [xpc_events(3) man page] xpcevents3man. With this API, it is relatively straightforward to write a launch agent (a background process) that will be launched on demand when a specific piece of hardware is connected (attached).