Core Data is probably one of the most misunderstood Frameworks on OS X and iOS. To help with that, we'll quickly go through Core Data to give you an overview of what it is all about, as understanding Core Data concepts is essential to using Core Data the right way. Just about all frustrations with Core Data originate in misunderstanding what it does and how it works. Let's dive in...

What is Core Data?

More than eight years ago, in April 2005, Apple released OS X version 10.4, which was the first to sport the Core Data framework. That was back when YouTube launched.

Core Data is a model layer technology. Core Data helps you build the model layer that represents the state of your app. Core Data is also a persistent technology, in that it can persist the state of the model objects to disk. But the important takeaway is that Core Data is much more than just a framework to load and save data. It's also about working with the data while it's in memory.

If you've worked with Object-relational mapping (O/RM) before: Core Data is not an O/RM. It's much more. If you've been working with SQL wrappers before: Core Data is not an SQL wrapper. It does by default use SQL, but again, it's a way higher level of abstraction. If you want an O/RM or SQL wrapper, Core Data is not for you.

One of the very powerful things that Core Data provides is its object graph management. This is one of the pieces of Core Data you need to understand and learn in order to bring the powers of Core Data into play.

On a side note: Core Data is entirely independent from any UI-level frameworks. It's, by design, purely a model layer framework. And on OS X it may make a lot of sense to use it even in background daemons and the like.

The Stack

There are quite a few components to Core Data. It's a very flexible technology. For most uses cases, the setup will be relatively simple.

When all components are tied together, we refer to them as the Core Data Stack. There are two main parts to this stack. One part is about object graph management, and this should be the part that you know well, and know how to work with. The second part is about persistence, i.e. saving the state of your model objects and retrieving the state again.

In between the two parts, in the middle of the stack, sits the Persistent Store Coordinator (PSC), also known to friends as the central scrutinizer. It ties together the object graph management part with the persistence part. When one of the two needs to talk to the other, this is coordinated by the PSC.

The object graph management is where your application's model layer logic will live. Model layer objects live inside a context. In most setups, there's one context and all objects live in that context. Core Data supports multiple contexts, though, for more advanced use cases. Note that contexts are distinct from one another, as we'll see in a bit. The important thing to remember is that objects are tied to their context. Each managed object knows which context it's in, and each context knows which objects it is managing.

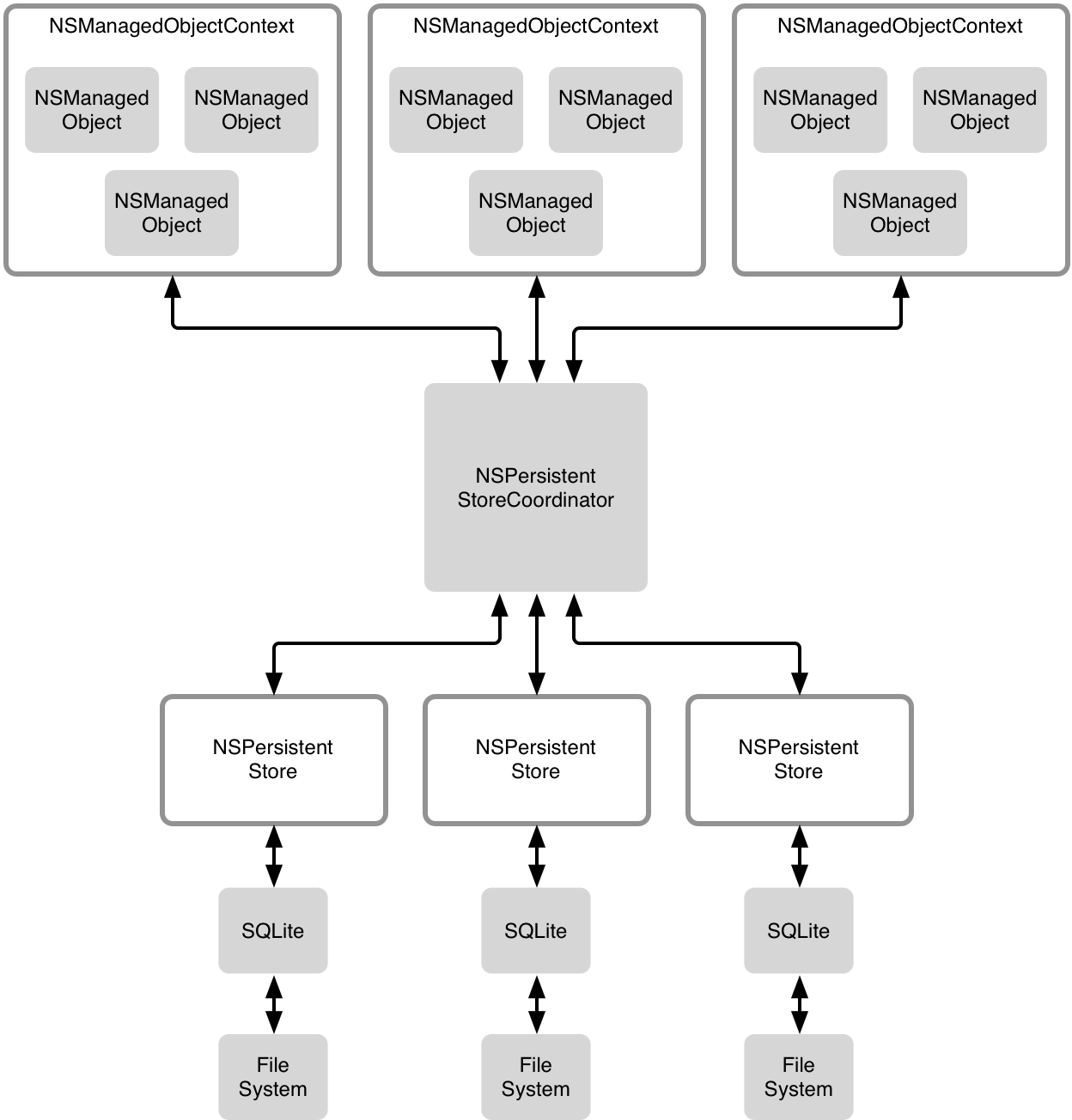

The other part of the stack is where persistency happens, i.e. where Core Data reads and writes from / to the file system. In just about all cases, the persistent store coordinator (PSC) has one so-called persistent store attached to it, and this store interacts with a SQLite database in the file system. For more advanced setups, Core Data supports using multiple stores that are attached to the same persistent store coordinator, and there are a few store types than just SQL to choose from.

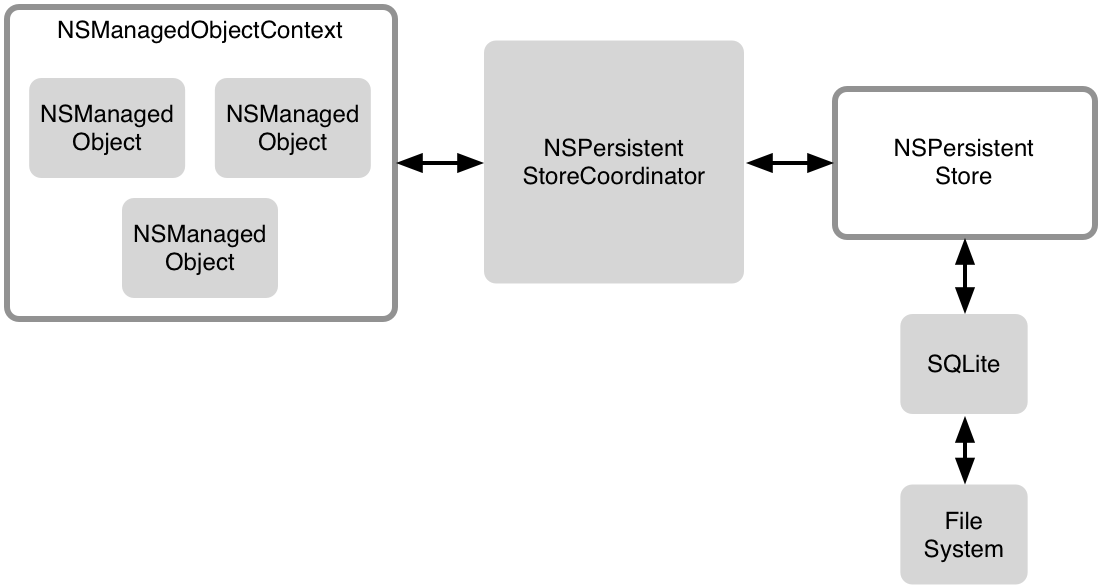

The most common scenario, however, looks like this:

How the Components Play Together

Let's quickly walk through an example to illustrate how these components play together. In our article about a full application using Core Data, we have exactly one entity, i.e. one kind of object: We have an Item entity that holds on to a title. Each item can have sub-items, hence we have a parent and a child relationship.

This is our data model. As we mention in the article about Data Models and Model Objects, a particular kind of object is called an Entity in Core Data. In this case we have just one entity: an Item entity. And likewise, we have a subclass of NSManagedObject which is called Item. The Item entity maps to the Item class. The data models article goes into more detail about this.

Our app has a single root item. There's nothing magical to it. It's simply an item we use to show the bottom of the item hierarchy. It's an item that we'll never set a parent on.

When the app launches, we set up our stack as depicted above, with one store, one managed object context, and a persistent store coordinator to tie the two together.

On first launch, we don't have any items. The first thing we need to do is to create the root item. You add managed objects by inserting them into the context.

Creating Objects

It may seem cumbersome. The way to insert objects is with the

+ (id)insertNewObjectForEntityForName:(NSString *)entityName

inManagedObjectContext:(NSManagedObjectContext *)context

method on NSEntityDescription. We suggest that you add two convenience methods to your model class:

+ (NSString *)entityName

{

return @“Item”;

}

+ (instancetype)insertNewObjectInManagedObjectContext:(NSManagedObjectContext *)moc;

{

return [NSEntityDescription insertNewObjectForEntityForName:[self entityName]

inManagedObjectContext:moc];

}

Now, we can insert our root object like so:

Item *rootItem = [Item insertNewObjectInManagedObjectContext:managedObjectContext];

Now there's a single item in our managed object context (MOC). The context knows about this newly inserted managed object and the managed object rootItem knows about the context (it has a -managedObjectContext method).

Saving Changes

At this point, though, we have not touched the persistent store coordinator or the persistent store, yet. The new model object, rootItem, is just in memory. If we want to save the state of our model objects (in this case just that one object), we need to save the context:

NSError *error = nil;

if (! [managedObjectContext save:&error]) {

// Uh, oh. An error happened. :(

}

At this point, a lot is going to happen. First, the managed object context figures out what has changed. It is the context's responsibility to track any and all changes you make to any managed objects inside that context. In our case, the only change we've made thus far is inserting one object, our rootItem.

The managed object context then passes these changes on to the persistent store coordinator and asks it to propagate the changes through to the store. The persistent store coordinator coordinates with the store (in our case, an SQL store) to write our inserted object into the SQL database on disk. The NSPersistentStore class manages the actual interaction with SQLite and generates the SQL code that needs to be executed. The persistent store coordinator's role is to simply coordinate the interaction between the store and the context. In our case, that role is relatively simple, but complex setups can have multiple stores and multiple contexts.

Updating Relationships

The power of Core Data is managing relationships. Let's look at the simple case of adding our second item and making it a child item of the rootItem:

Item *item = [Item insertNewObjectInManagedObjectContext:managedObjectContext];

item.parent = rootItem;

item.title = @"foo";

That's it. Again, these changes are only inside the managed object context. Once we save the context, however, the managed object context will tell the persistent store coordinator to add that newly created object to the database file just like for our first object. But it will also update the relationship from our second item to the first and the other way around, from the first object to the second. Remember how the Item entity has a parent and a children relationship. These are reverse relationships of one another. Because we set the first item to be the parent of the second, the second will be a child of the first. The managed object context tracks these relationships and the persistent store coordinator and the store persist (i.e. save) these relationships to disk.

Getting to Objects

Let's say we've been using our app for a while and have added a few sub-items to the root item, and even sub-items to the sub-items. Then we launch our app again. Core Data has saved the relationships of the items in the database file. The object graph is persisted. We now need to get to our root item, so we can show the bottom-level list of items. There are two ways for us to do that. We'll look at the simpler one first.

When we created our rootItem object, and once we've saved it, we can ask it for its NSManagedObjectID. This is an opaque object that uniquely represents that object. We can store this into e.g. NSUSerDefaults, like this:

NSUserDefaults *defaults = [NSUserDefaults standardUserDefaults];

[defaults setURL:rootItem.managedObjectID.URIRepresentation forKey:@"rootItem"];

Now when the app is relaunched, we can get back to the object like so:

NSUserDefaults *defaults = [NSUserDefaults standardUserDefaults];

NSURL *uri = [defaults URLForKey:@"rootItem"];

NSManagedObjectID *moid = [managedObjectContext.persistentStoreCoordinator managedObjectIDForURIRepresentation:uri];

NSError *error = nil;

Item *rootItem = (id) [managedObjectContext existingObjectWithID:moid error:&error];

Obviously, in a real app, we'd have to check if NSUserDefaults actually returns a valid value.

What just happened is that the managed object context asked the persistent store coordinator to get that particular object from the database. The root object is now back inside the context. However, all the other items are not in memory, yet.

The rootItem has a relationship called children. But there's nothing there, yet. We want to display the sub-items of our rootItem, and hence we'll call:

NSOrderedSet *children = rootItem.children;

What happens now, is that the context notes that the relationship children from that rootItem is a so-called fault. Core Data has marked the relationship as something it still has to resolve. And since we're accessing it at this point, the context will now automatically coordinate with the persistent store coordinator to bring those child items into the context.

This may sound very trivial, but there's actually a lot going on at this point. If any of the child objects happen to already be in memory, Core Data guarantees that it will reuse those objects. That's what is called uniquing. Inside the context, there's never going to be more than a single object representing a given item.

Secondly, the persistent store coordinator has its own internal cache of object values. If the context needs a particular object (e.g. a child item), and the persistent store coordinator already has the needed values in its cache, the object (i.e. the item) can be added to the context without talking to the store. That's important, because accessing the store means running SQL code, which is much slower than using values already in memory.

As we continue to traverse from item to sub-item to sub-item, we're slowly bringing the entire object graph into the managed object context. Once it's all in memory, operating on objects and traversing the relationships is super fast, since we're just working inside the managed object context. We don't need to talk to the persistent store coordinator at all. Accessing the title, parent, and children properties on our Item objects is super fast and efficient at this point.

It's important to understand how data is fetched in these cases, since it affects performance. In our particular case, it doesn't matter too much, since we're not touching a lot of data. But as soon as you do, you'll need to understand what goes on under the hood.

When you traverse a relationship (such as parent or children in our case) one of three things can happen: (1) the object is already in the context and traversing is basically for free. (2) The object is not in the context, but the persistent store coordinator has its values cached, because you've recently retrieved the object from the store. This is reasonably cheap (some locking has to occur, though). The expensive case is (3) when the object is accessed for the first time by both the context and the persistent store coordinator, such that is has to be retrieved by store from the SQLite database. This last case is much more expensive than (1) and (2).

If you know you have to fetch objects from the store (because you don't have them), it makes a huge difference when you can limit the number of fetches by getting multiple objects at once. In our example, we might want to fetch all child items in one go instead of one-by-one. This can be done by crafting a special NSFetchRequest. But we must take care to only to run a fetch request when we need to, because a fetch request will also cause option (3) to happen; it will always access the SQLite database. Hence, when performance matters, it makes sense to check if objects are already around. You can use -[NSManagedObjectContext objectRegisteredForID:] for that.

Changing Object Values

Now, let's say we are changing the title of one of our Item objects:

item.title = @"New title";

When we do this, the items title changes. But additionally, the managed object context marks the specific managed object (item) as changed, such that it will be saved through the persistent store coordinator and attached store when we call -save: on the context. One of the key responsibilities of the context is change tracking.

The context knows which objects have been inserted, changed, and deleted since the last save. You can get to those with the -insertedObjects, -updatedObjects, and -deletedObjects methods. Likewise, you can ask a managed object which of its values have changed by using the -changedValues method. You will probably never have to. But this is what Core Data uses to be able to push changes you make to the backing database.

When we inserted new Item objects above, this is how Core Data knew it had to push those to the store. And now, when we changed the title, the same thing happened.

Saving values needs to coordinate with both the persistent store coordinator and the persistent store, which, in turn, accesses the SQLite database. As when retrieving objects and values, accessing the store and database is relatively expensive when compared to simply operating on objects in memory. There's a fixed cost for a save, regardless of how many changes you're saving. And there's a per-change cost. This is simply how SQLite works. When you're changing a lot of things, you should therefore try to batch changes into reasonably sized batches. If you save for each change, you'd pay a high price, because you have to save very often. If you save too rarely, you'd have a huge batch of changes that SQLite would have to process.

It is also important to note that saves are atomic. They're transactional. Either all changes will be committed to the store / SQLite database or none of the changes will be saved. This is important to keep in mind when implementing custom NSIncrementalStore subclasses. You have to either guarantee that a save will never fail (e.g. due to conflicts), or your store subclass has to revert all changes when the save fails. Otherwise, the object graph in memory will end up being inconsistent with the one in the store.

Saves will normally never fail if you use a simple setup. But Core Data allows multiple contexts per persistent store coordinator, so you can run into conflicts at the persistent store coordinator level. Changes are per-context, and another context may have introduced conflicting changes. And Core Data even allows for completely separate stacks both accessing the same SQLite database file on disk. That can obviously also lead to conflicts (i.e. one context trying to update a value on an object that was deleted by another context). Another reason why a save can fail is validation. Core Data supports complex validation policies for objects. It's an advanced topic. A simple validation rule could be that the title of an Item must not be longer than 300 characters. But Core Data also supports complex validation policies across properties.

Final Words

If Core Data seems daunting, that's most likely because its flexibility allows you to use it in very complex ways. As always: try to keep things as simple as possible. It will make development easier and save you and your user from trouble. Only use the more complex things such as background contexts if you're certain they will actually help.

When you're using a simple Core Data stack, and you use managed objects the way we've tried to outline in this issue, you'll quickly learn to appreciate what Core Data can do for you, and how it speeds up your development cycle.