Singletons are one of the core design patterns used throughout Cocoa. In fact, Apple's Developer Library considers the singleton one of the "Cocoa Core Competencies." As iOS developers, we're familiar with interacting with singletons, from UIApplication to NSFileManager. We've seen countless examples of singleton usage in open-source projects, in Apple's code samples, and on StackOverflow. Xcode even has a default code snippet, the "Dispatch Once" snippet, which makes it incredibly easy to add a singleton to your code:

+ (instancetype)sharedInstance

{

static dispatch_once_t once;

static id sharedInstance;

dispatch_once(&once, ^{

sharedInstance = [[self alloc] init];

});

return sharedInstance;

}

For these reasons, singletons are commonplace in iOS programming. The problem is that they're easy to abuse.

While others have called singletons an 'anti-pattern,' 'evil,' and 'pathological liars', I won't completely rule out the merit of singletons. Instead, I want to demonstrate a few problems with singletons so that the next time you're about to auto-complete that dispatch_once snippet, you think twice about the implications.

Global State

Most developers agree that global mutable state is a bad thing. Statefulness makes programs hard to understand and hard to debug. We object-oriented programmers have much to learn from functional programming, in terms of minimizing the statefulness of code.

@implementation SPMath {

NSUInteger _a;

NSUInteger _b;

}

- (NSUInteger)computeSum

{

return _a + _b;

}

In the above implementation of a simple math library, the programmer is expected to set instance variables _a and _b to the proper values before invoking computeSum. There are a few problems here:

-

computeSumdoes not make the fact that it depends upon states_aand_bexplicit by taking the values as parameters. Instead of inspecting the interface and understanding which variables control the output of the function, another developer reading this code must inspect the implementation to understand the dependency. Hidden dependencies are bad. -

When modifying

_aand_bin preparation for callingcomputeSum, the programmer needs to be sure the modification does not affect the correctness of any other code that depends upon these variables. This is particularly difficult in multi-threaded environments.

Contrast the above example with this:

+ (NSUInteger)computeSumOf:(NSUInteger)a plus:(NSUInteger)b

{

return a + b;

}

Here, the dependency on a and b is made explicit. We don't need to mutate instance state in order to call this method. And we don't need to worry about leaving behind persistent side effects as a result of calling this method. As a note to the reader of this code, we can even make this method a class method to indicate that it does not modify instance state.

So how does this example relate to singletons? In the words of Miško Hevery, "Singletons are global state in sheep’s clothing." A singleton can be used anywhere, without explicitly declaring the dependency. Just like _a and _b were used in computeSum without the dependency being made explicit, any module of the program can call [SPMySingleton sharedInstance] and get access to the singleton. This means any side effects of interacting with the singleton can affect arbitrary code elsewhere in the program.

@interface SPSingleton : NSObject

+ (instancetype)sharedInstance;

- (NSUInteger)badMutableState;

- (void)setBadMutableState:(NSUInteger)badMutableState;

@end

@implementation SPConsumerA

- (void)someMethod

{

if ([[SPSingleton sharedInstance] badMutableState]) {

// ...

}

}

@end

@implementation SPConsumerB

- (void)someOtherMethod

{

[[SPSingleton sharedInstance] setBadMutableState:0];

}

@end

In the example above, SPConsumerA and SPConsumerB are two completely independent modules of the program. Yet SPConsumerB is able to affect the behavior of SPConsumerA through the shared state provided by the singleton. This should only be possible if consumer B is given an explicit reference to A, making clear the relationship between the two. The singleton here, due to its global and stateful nature, causes hidden and implicit coupling between seemingly unrelated modules.

Let's take a look at a more concrete example, and expose one additional problem with global mutable state. Let's say we want to build a web viewer inside our app. To support this web viewer, we build a simple URL cache:

@interface SPURLCache

+ (SPCache *)sharedURLCache;

- (void)storeCachedResponse:(NSCachedURLResponse *)cachedResponse forRequest:(NSURLRequest *)request;

@end

The developer working on the web viewer starts writing some unit tests to make sure the code works as expected in a few different situations. First, he or she writes a test to make sure the web viewer shows an error when there's no device connectivity. Then he or she writes a test to make sure the web viewer handles server failures properly. Finally, he or she writes a test for the basic success case, to make sure the returned web content is shown properly. The developer runs all of the tests, and they work as expected. Nice!

A few months later, these tests start failing, even though the web viewer code hasn't changed since it was first written! What happened?

It turns out someone changed the order of the tests. The success case test is running first, followed by the other two. The error cases are now succeeding unexpectedly, because the singleton URL cache is caching the response across the tests.

Persistent state is the enemy of unit testing, since unit testing is made effective by each test being independent of all other tests. If state is left behind from one test to another, then the order of execution of tests suddenly matters. Buggy tests, especially when a test succeeds when it shouldn't, are a very bad thing.

Object Lifecycle

The other major problem with singletons is their lifecycle. When adding a singleton to your program, it's easy to think, "There will only ever be one of these." But in much of the iOS code I've seen in the wild, that assumption can break down.

For example, suppose we're building an app where users can see a list of their friends. Each of their friends has a profile picture, and we want the app to be able to download and cache those images on the device. With the dispatch_once snippet handy, we might find ourselves writing an SPThumbnailCache singleton:

@interface SPThumbnailCache : NSObject

+ (instancetype)sharedThumbnailCache;

- (void)cacheProfileImage:(NSData *)imageData forUserId:(NSString *)userId;

- (NSData *)cachedProfileImageForUserId:(NSString *)userId;

@end

We continue building out the app, and all seems well in the world, until one day, when we decide it's time to implement the 'log out' functionality, so users can switch accounts inside the app. Suddenly, we have a nasty problem on our hands: user-specific state is stored in a global singleton. When the user signs out of the app, we want to be able to clean up all persistent states on disk. Otherwise, we'll leave behind orphaned data on the user's device, wasting precious disk space. In case the user signs out and then signs into a new account, we also want to be able to have a new SPThumbnailCache for the new user.

The problem here is that singletons, by definition, are assumed to be "create once, live forever" instances. You could imagine a few solutions to the problem outlined above. Perhaps we could tear down the singleton instance when the user signs out:

static SPThumbnailCache *sharedThumbnailCache;

+ (instancetype)sharedThumbnailCache

{

if (!sharedThumbnailCache) {

sharedThumbnailCache = [[self alloc] init];

}

return sharedThumbnailCache;

}

+ (void)tearDown

{

// The SPThumbnailCache will clean up persistent states when deallocated

sharedThumbnailCache = nil;

}

This is a flagrant abuse of the singleton pattern, but it will work, right?

We could certainly make this solution work, but the cost is far too great. For one, we've lost the simplicity of the dispatch_once solution, a solution which guarantees thread safety and that all code calling [SPThumbnailCache sharedThumbnailCache] only ever gets the same instance. We now need to be extremely careful about the order of code execution for code that utilizes the thumbnail cache. Suppose while the user is in the process of signing out, there's some background task that is in the process of saving an image into the cache:

dispatch_async(dispatch_get_global_queue(DISPATCH_QUEUE_PRIORITY_DEFAULT, 0), ^{

[[SPThumbnailCache sharedThumbnailCache] cacheProfileImage:newImage forUserId:userId];

});

We need to be certain tearDown doesn't execute until after that background task completes. This ensures the newImage data will get cleaned up properly. Or, we need to make sure the background task is canceled when the thumbnail cache is shut down. Otherwise, a new thumbnail cache will be lazily created, and stale user state (the newImage) will be stored inside of it.

Since there's no distinct owner for the singleton instance (i.e. the singleton manages its own lifecycle), it becomes very difficult to ever 'shut down' a singleton.

At this point, I hope you're saying, "The thumbnail cache shouldn't have ever been a singleton!" The problem is that an object's lifecycle may not be fully understood at the start of a project. As a concrete example, the Dropbox iOS app only ever had support for a single user account to be signed into. The app existed in this state for years, until one day when we wanted to support multiple user accounts (both personal and business accounts) to be signed in simultaneously. All of a sudden, assumptions that "there will only ever be a single user signed in at a time" started to break down. By assuming an object's lifecycle will match the lifecycle of your application, you'll limit the extensibility of your code, and you may need to pay for that assumption later when product requirements change.

The lesson here is that singletons should be preserved only for state that is global, and not tied to any scope. If state is scoped to any session shorter than "a complete lifecycle of my app," that state should not be managed by a singleton. A singleton that's managing user-specific state is a code smell, and you should critically reevaluate the design of your object graph.

Avoiding Singletons

So, if singletons are so bad for scoped state, how do we avoid using them?

Let's revisit the example above. Since we have a thumbnail cache that caches state specific to an individual user, let's define a user object:

@interface SPUser : NSObject

@property (nonatomic, readonly) SPThumbnailCache *thumbnailCache;

@end

@implementation SPUser

- (instancetype)init

{

if ((self = [super init])) {

_thumbnailCache = [[SPThumbnailCache alloc] init];

// Initialize other user-specific state...

}

return self;

}

@end

We now have an object to model an authenticated user session, and we can store all user-specific state under this object. Now suppose we have a view controller that renders the list of friends:

@interface SPFriendListViewController : UIViewController

- (instancetype)initWithUser:(SPUser *)user;

@end

We can explicitly pass the authenticated user object into the view controller. This technique of passing a dependency into a dependent object is more formally referred to as dependency injection, and it has ton of advantages:

-

It makes clear to the reader of this interface that the

SPFriendListViewControllershould only ever be shown when there's a signed-in user. -

The

SPFriendListViewControllercan maintain a strong reference to the user object as long as it's being used. For instance, updating the earlier example, we can save an image into the thumbnail cache within a background task as follows:

dispatch_async(dispatch_get_global_queue(DISPATCH_QUEUE_PRIORITY_DEFAULT, 0), ^{

[_user.thumbnailCache cacheProfileImage:newImage forUserId:userId];

});

With this background task still outstanding, code elsewhere in the application is able to create and utilize an entirely new SPUser object, without blocking further interaction while the first instance is being torn down.

To demonstrate the second point a little further, let's visualize the object graph before and after using dependency injection.

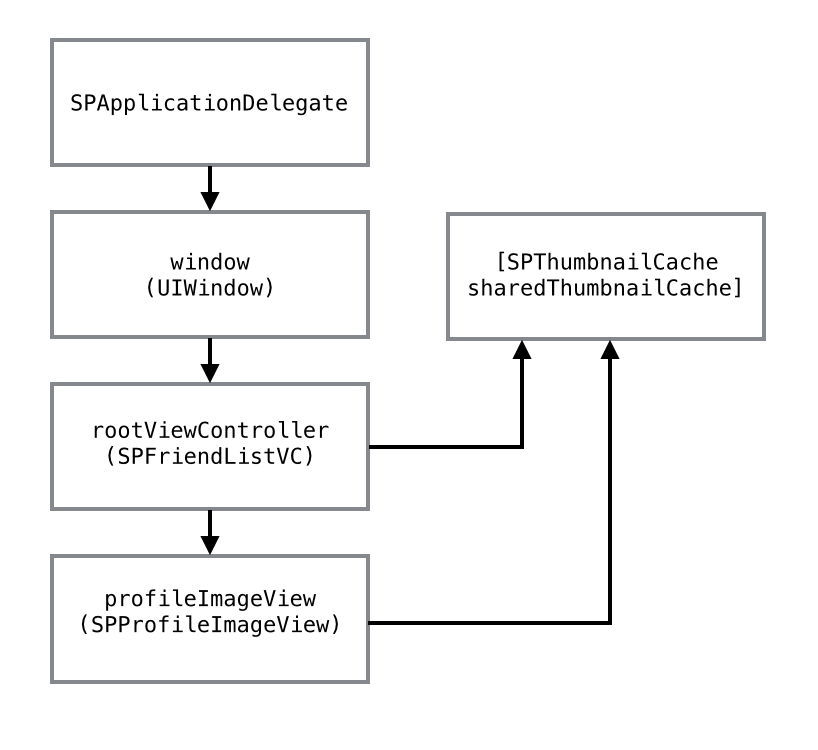

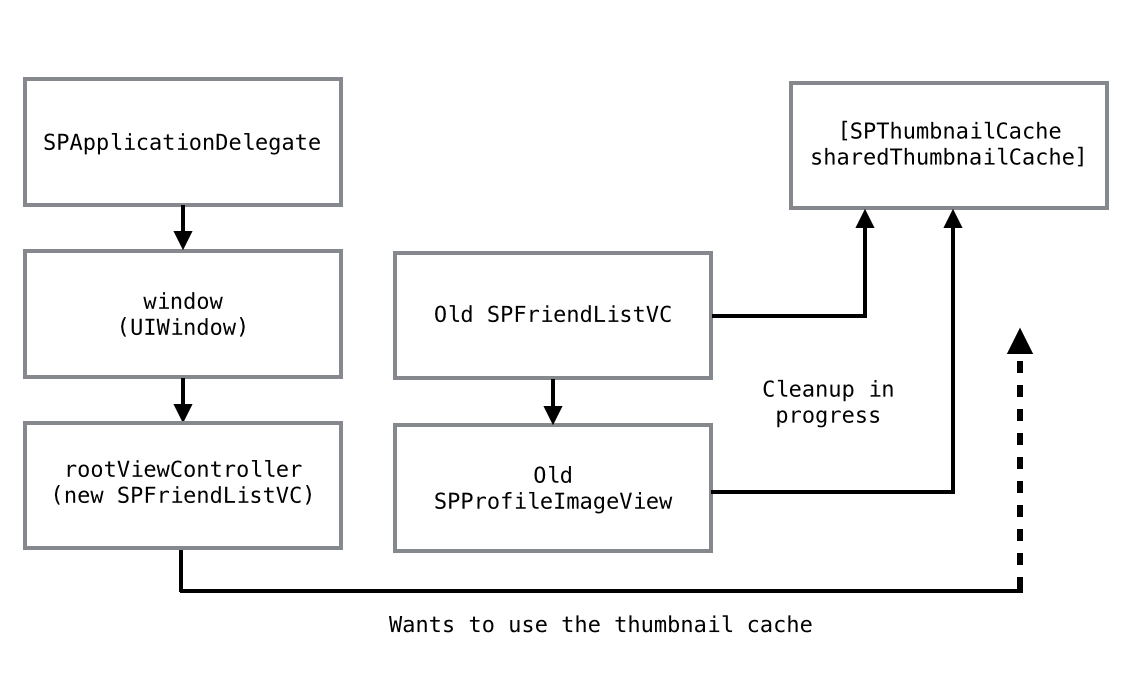

Suppose our SPFriendListViewController is currently the root view controller in the window. With the singleton model, we have an object graph that looks like this:

The view controller itself, along with a list of custom image views, interacts with the sharedThumbnailCache. When the user logs out, we want to clear the root view controller and take the user back to a sign-in screen:

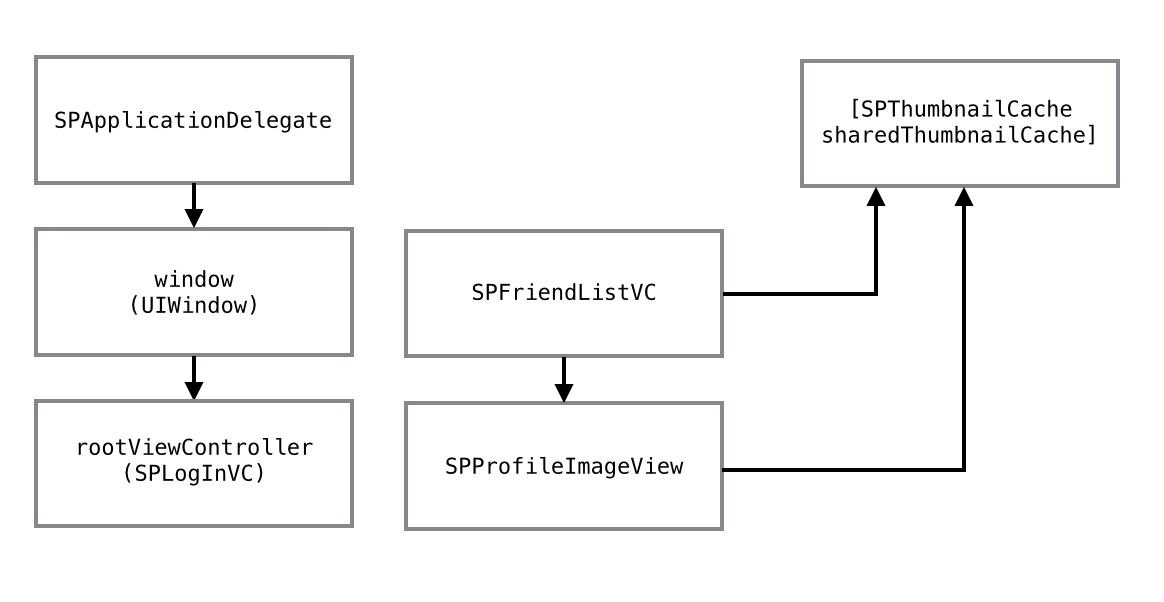

The problem here is that the friend list view controller might still be executing code (due to background operations), and therefore may still have outstanding calls pending to the sharedThumbnailCache.

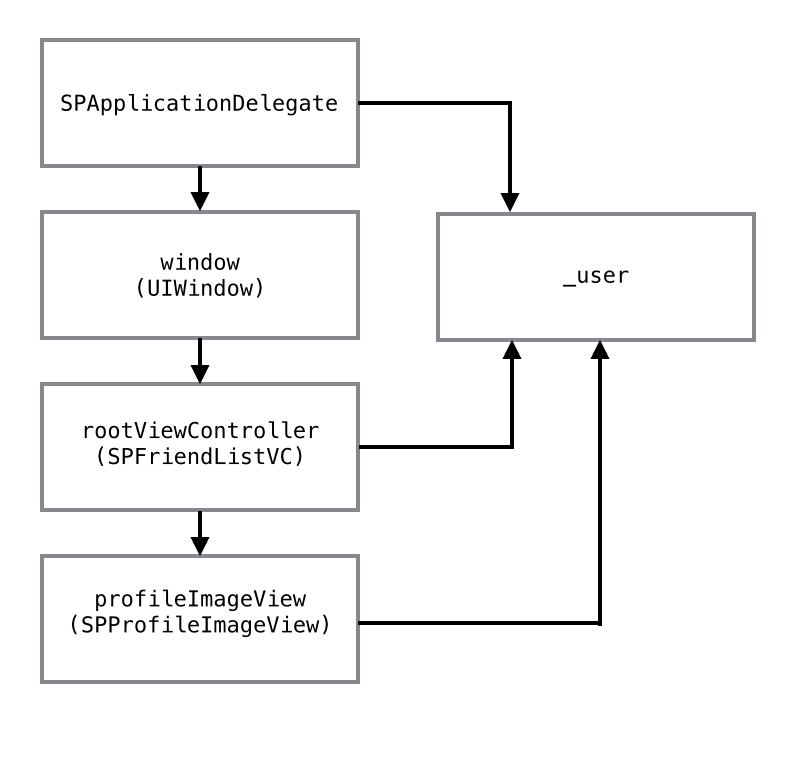

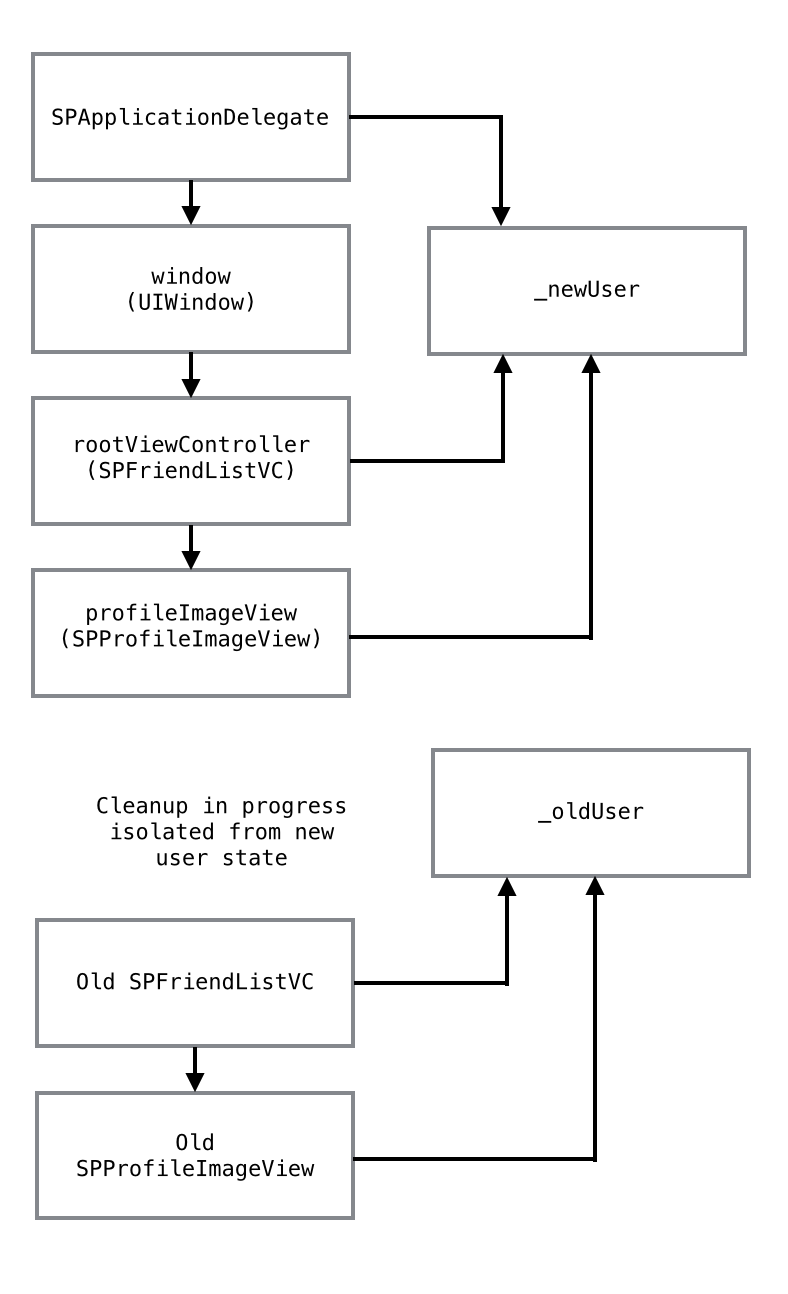

Contrast this with the solution that utilizes dependency injection:

Suppose, for simplicity, that the SPApplicationDelegate manages the SPUser instance (in practice, you probably want to offload such user state management to another object to keep your application delegate lighter). When the friend list view controller is installed in the window, a reference to the user is passed. This reference can be funneled down the object graph to the profile image views as well. Now, when the user logs out, our object graph looks like this:

The object graph looks pretty similar to the case in which we used a singleton. So what's the big deal?

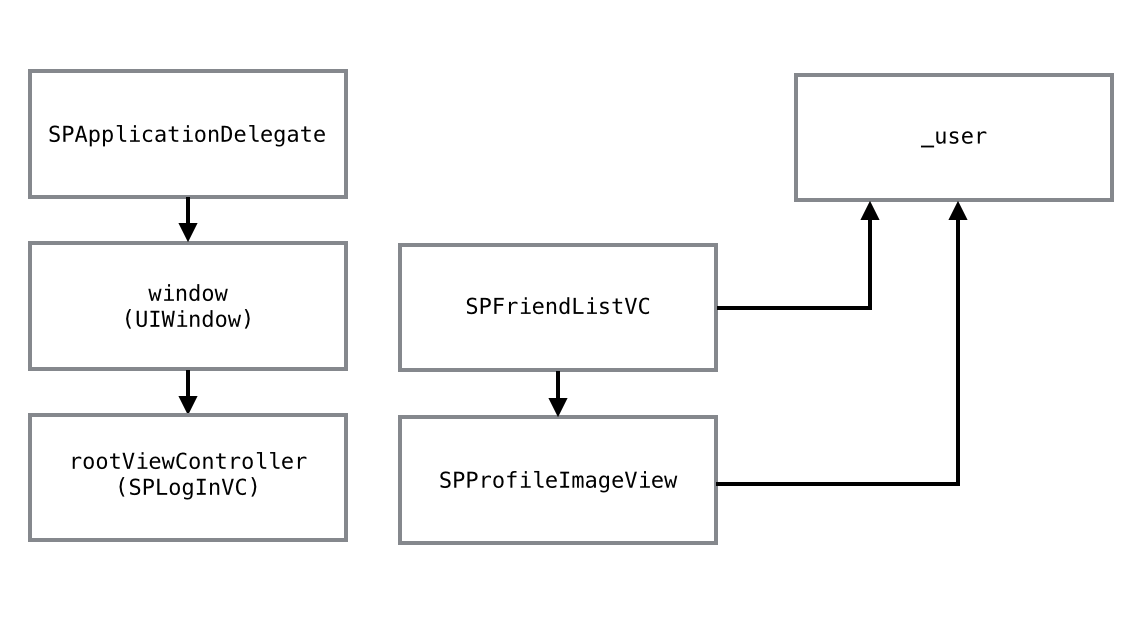

The problem is scope. In the singleton case, the sharedThumbnailCache is still accessible to arbitrary modules of the program. Suppose the user quickly signs in to a new account. The new user will want to see his or her friends, too, which means interacting with the thumbnail cache again:

When the user signs in to a new account, we should be able to construct and interact with a brand new SPThumbnailCache, with no attention paid to the destruction of the old thumbnail cache. The old view controllers and old thumbnail cache should be cleaned up lazily in the background on their own accord, based on the typical rules of object management. In short, we should isolate the state associated with user A from the state associated with user B:

Conclusion

Hopefully nothing in this article reads as particularly novel. People have been complaining about the abuse of singletons for years and we all know global state is bad. But in the world of iOS development, singletons are so commonplace that we can sometimes forget the lessons learned from years of object-oriented programming elsewhere.

The key takeaway from all of this is that in object-oriented programming we want to minimize the scope of mutable state. Singletons stand in direct opposition to that, since they make mutable state accessible from anywhere in the program. The next time you think to use a singleton, I hope you consider dependency injection as an alternative.